Neurosurgery Research

Neurosurgery is at the frontier of medical science working to discover the secrets of the brain to better understand and treat patients. Learn more about the Department of Neurosurgery.

About

One of the most concerning experiences is hearing that you or a loved one is being referred to a brain surgeon.

Brain or spine diseases such as cancer, epilepsy or chronic pain can be physically and mentally taxing on patients and their loved ones during all stages of disease progression. The home health care needs sometimes associated with brain conditions requiring surgery can add considerable financial and social burdens.

The Carilion Clinic Neurosurgery team is committed to providing the best care possible—support, education and treatment—to optimize every patient's quality of life. We believe that this philosophy includes the pursuit of new ideas and innovations to better investigate and bring new technologies to help heal our community.

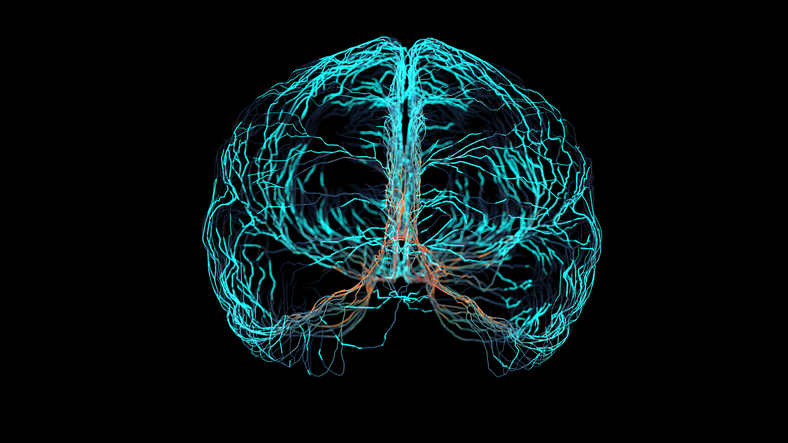

When asked why they become neurosurgeons, many doctors will mention the beauty of the "black box" called the brain. The brain is not only a biological computer, running the human body; it is also responsible for our personalities, memories and core selves. Each brain and thus each person is unique. Much remains unknown about the brain and how all the individual pieces work together to create the wonderful being that is a human person.

Our neurosurgical team is dedicated to exploring the brain and its secrets; finding new ways to understand the healthy brain and disease; and helping to create the newest, advanced treatments for our patients.

"At Virginia Tech Carilion Neurosurgery, we believe that clinical, translational and basic science research are fundamental to the development of the field of neurosurgery. To this end, we focus many resources on developing our faculty and trainees as research thought leaders. To accomplish this, we participate in many investigator sponsored studies as well as clinical trials, and regularly host visiting faculty to foster the development and interchange of new ideas."

Mark Witcher, MD, PhD

Resident Program Director

Common Conditions

Neurosurgeons treat a variety of complex conditions relating to the brain, nerves and nervous system, as well as its supporting structure, such as brain and spine. Some of the more common conditions can be broken down into the following categories:

- Brain or cranial swelling

- Cancers

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Congenital conditions

- Movement disorders (e.g., Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, etc.)

- Nervous system infections

- Pain disorders

- Spinal disorders (including degenerative disc/vertebral body disorders)

- Traumatic injuries

- Vascular disorders (e.g., stroke, hemorrhages, hypertension, aneurysms)

Current Research

Neurosurgery research is as varied and far-reaching as the conditions neurosurgeons treat, and our portfolio of ongoing research is continually growing. Highlighted below are some of the prominent areas of our current neurosurgery research in the areas of:

- Cancer

- Imaging

- Innovation

- Movement Disorders

- Pain

- Traumatic Injury

- Vascular

Cancer

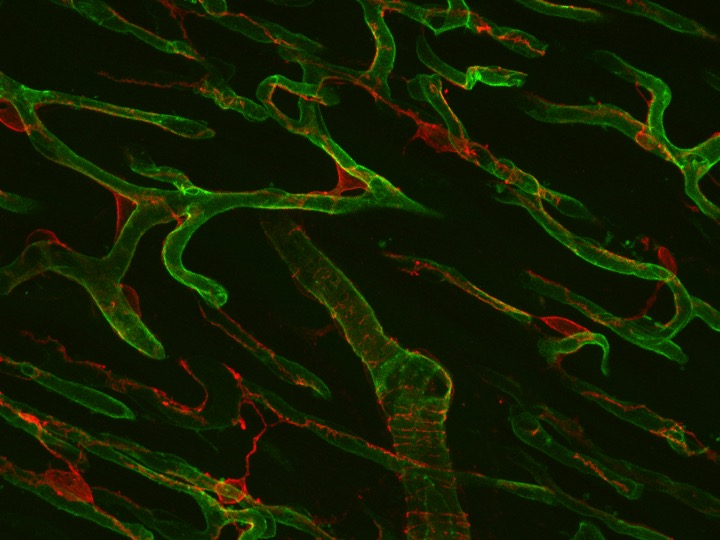

Patient-Derived Tissue-Engineered Systems With Physiological Flow to Study Glioblastoma

PI: Mark Witcher, MD, PhD

Collaboration with Jenny Munson, PhD, Virginia Tech

Cancers in the brain are difficult to treat. Efforts to identify new treatments for glioblastoma (GBM), the most common malignant and deadly brain cancer, have stagnated since the creation of the highly successful chemotherapy drug, temozolomide, in 2005 that largely improved survival and treatment. Since then, little has been accomplished to increase survival in patients with GBM.

Most studies of GBM in research labs have focused on the cells of the cancerous tissue themselves, rather than the location and characteristics of the environment of the tumor. To improve our experiments and the relevance of our results, we have invented a new study system—the tumor microenvironment (TME)—where we make our samples with tumor cells in conjunction with other normal brain cells to recreate the way the tumor cells and normal brain cells interact.

In this research, we will collect the brain tumor tissues and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that would both otherwise be discarded after surgery. The amount of CSF collected will vary depending on the procedure of the voluntary participant. We will generate TME samples with cells isolated from these collected patient samples, then treat the samples in the laboratory with temozolomide and radiation, mimicking the standard treatment that patients receive for GBM. We will measure the response of the TME samples by seeing how much tumor cells travel and go through cell death, then compare the treatment-induced changes in the experimental samples with the course and outcome of the actual patient’s GBM disease from clinical treatment after surgery.

By comparing the responses of the TME samples to the patient’s outcome, we will determine if our TME sample system will be able to predict the patient's response to treatment.

At the conclusion of this study, we will have the data and information needed to propose a clinical trial in which we would set up our patient TME samples and treat with standard post-surgery treatment for GBM (chemotherapy and radiation) and provide the results to the treating physicians so that they can consider altering the patient’s treatment with hopes of improving patient outcomes and course of disease.

Imaging

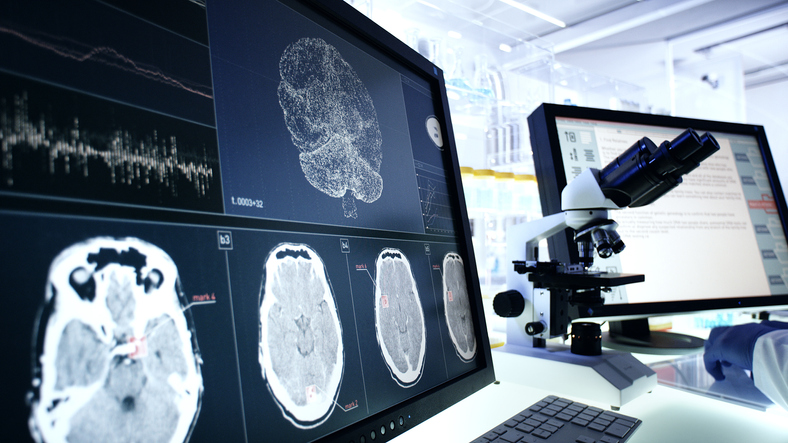

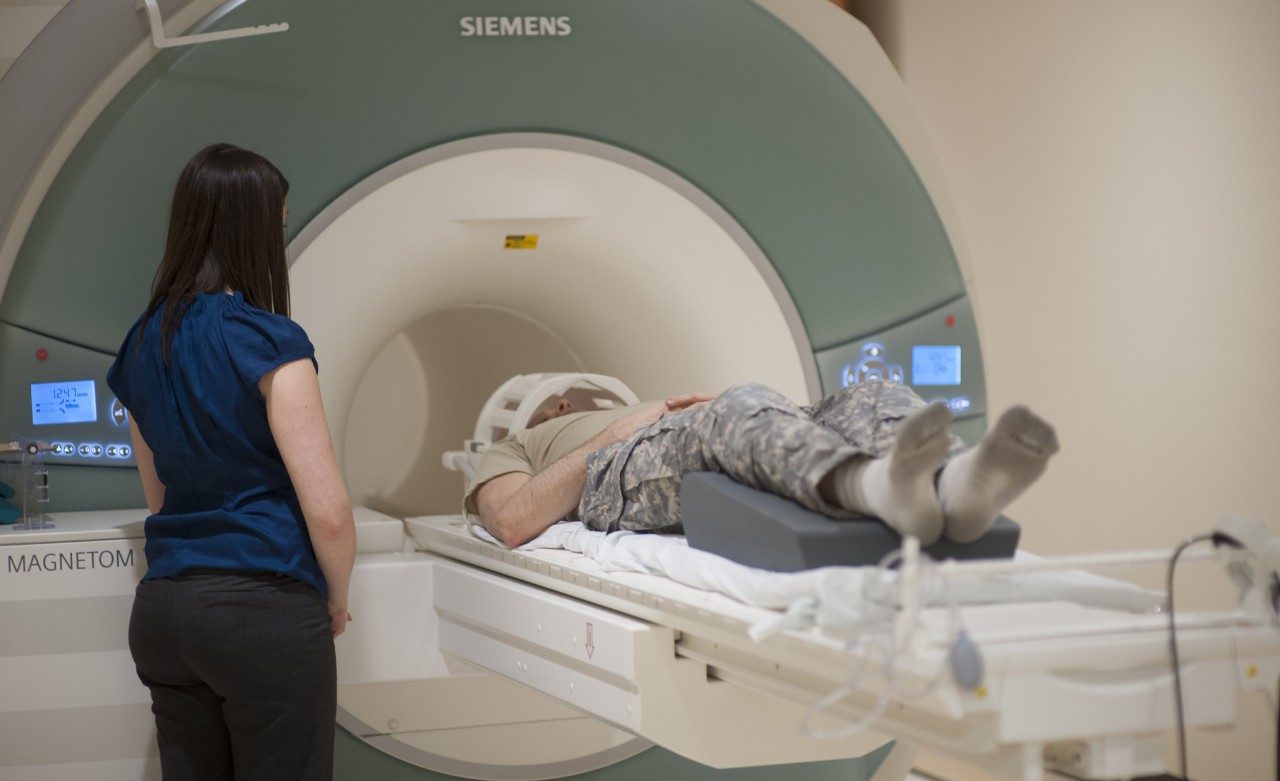

PET-based Imaging of High-Grade Gliomas using Gallium-labeled Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA)

PI: Mark Witcher, MD, PhD

Humans with high-grade gliomas—tumors of the brain or spinal cord—have a poor prognosis, with an average survival time of just 12-18 months for patients who undergo standard tumor removal and traditional radiation and/or chemotherapy.

Currently, surgery and chemoradiotherapy serve as standard treatment for this condition, yet these can be complicated by the tumor location, growth rate and recurrence. A recurrent tumor can often be very difficult to distinguish using conventional gadolinium-based MRI imaging, given its similarity in appearance to normal radiation-induced changes.

Despite these shortcomings, MRI serves as the dominant imaging technique, which likely doesn’t reveal the entirety of a tumor’s profile (de novo or recurrent) due to limitations inherent to gadolinium contrast, the current contrast dyes used to improve MRI image quality. Other imaging modalities, including PET, could play a significant role in the workup and treatment of these tumors.

To this end, we must identify PET-based markers for use in imaging of high-grade gliomas. Gallium-labeled prostate-specific membrane antigen (68Ga-PSMA) has demonstrated success as an effective target often associated with high-grade gliomas and will be evaluated in this study to diagnose these tumors.

Innovation

Local, Biodegradable, Sustained-Release Drug-Delivery System for Prevention of Chronic Subdural Hematoma (cSDH) Recurrence

PIs: Kristine Ravina, MD, and Eric Marvin, DO

Collaboration with Abby Whittington, PhD, Virginia Tech

Chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH), or long-term brain bleeding, is one of the most common neurosurgical diseases. It involves blood buildup in the space below the skull, typically due to initial connective vein tear that has worsened over a period of at least 3 weeks. This process usually involves breakdown of the blood products, membrane formation and development of long-term inflammatory changes.

The incidence of cSDH dramatically increases in those aged 70 years or older. Recurrent cSDH is reported in 10–25% of patients after surgical evacuation and can lead to devastating long-term consequences. Few studies to date have reported effectiveness of wholistic anti-inflammatory treatment in cSDH, such as corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone and prednisone) that, while demonstrating promising decrease in recurrence rates in some studies, have without fail been followed by systemic (whole body) side-effects and increased death rates. To date, there have been no reports of potential local (site of bleed) drug-delivery system use in cSDH patients to reduce recurrence rates and side effects from systemic use.

The idea of incorporating a commonly used antibiotic and an anti-inflammatory corticosteroid in a local drug delivery system is attractive given their individual robust effects on the core processes involved in cSDH. Additionally, the use of currently FDA approved medications and drug delivery systems/concepts has the potential in streamlining in-human clinical trials and rapid commercialization of these products for wide-spread use. Given cSDH are often requiring intense surgical evacuation via burr holes or a craniotomy, it allows for a unique window of local drug delivery system application thus avoiding an additional surgery to deliver the new drug to the site of cSDH.

____________

Retractor Project

PI: Adeolu Olasunkanmi, MD

____________

Novel Dural Sealant

PIs: Adeolu Olasunkanmi, MD

Collaboration with John Matson, PhD, and Michael Schulz, PhD, Virginia Tech

Dural tears-ruptures in the membrane (dura mater) that surrounds the brain and spinal cord-are one of the most challenging complications during neurosurgery, occurring during lumbar spinal surgery, for example, in 3.1-17.4% of cases. Inevitably, dural tears result in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage, increasing risk of infections and complications. To mitigate these complications, surgical materials have been developed to repair dural tears, including sutures, fibrin-adhesive sealants, and gel foam; however, a fully effective approach to mitigating CSF leaks remains elusive. Commercially available sealants, covalent bonds form between the amines in the underlying dural tissue and the NHS-esters in the formulation, producing an adhesive hydrogel. PEG-based sealants are hydrophilic and consequently swell in aqueous or humid environments, resulting in water uptake ranging from 87-558%. This swelling limits certain applications of these products. For example, commercially-available dural sealants are contraindicated for use in confined bony structures where nerves and spinal cord are present because hydrogel swelling may produce neural compression. PEG-based sealants, and other polyether-based materials, are also not fully biodegradable.

The goal of this work is to develop novel, improved materials for sealing dural tears. Most commercial dural sealants are based on legacy materials that were never specifically developed for neurosurgical applications. Consequently, current dural sealants are inherently limited by the underlying molecular structure of the materials themselves. As working with collaborator polymer synthesis group at VT, they will tune the molecular structure of the sealant material to balance dural adhesion, cohesive (internal) strength, CSF resistance, and ease of application.

____________

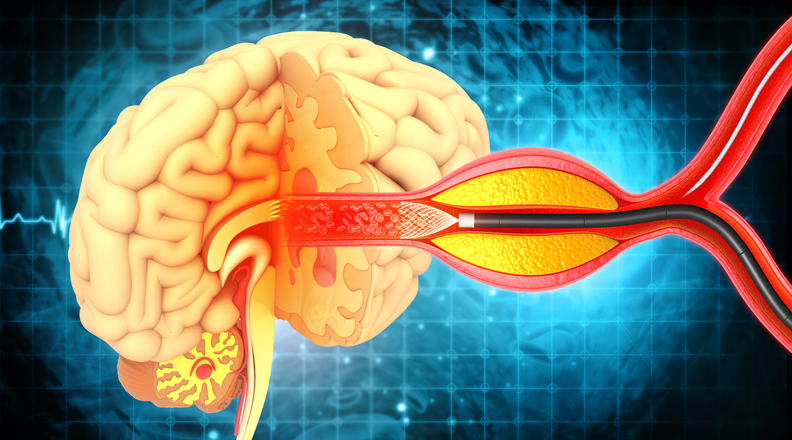

Flow Sensor for Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) Shunt Project

PI: Mark Witcher, MD, PhD

Having a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can cause certain brain conditions that require drainage of the fluid to prevent more serious conditions. Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) Shunts are simple systems that drain excess CSF once implanted. The CSF is released into tissue in the abdomen which can manage CSF and effectively dispose of it. This shunt system is implanted underneath the skin and flow is regulated by the valve. Current editions of this technology are purely based on buildup of CSF, as the catheters are passive components, and the valve is either physically self-managed through changes in pressure or externally managed using a magnetic system. This shunt system can be prone to issues arising from infection and blockages within the shunt line that aren’t detected by the passive system. Typically, patients will then present in the emergency department extremely ill and requiring a second procedure to replace the shunt system. We are interested in adding a flow rate monitor and a wireless information relay to monitor the shunt’s effectiveness and prevent patients from becoming ill or having poor outcomes from a failing device.

In this study, a device will be placed in the external drain line (catheter) of patients that have had a shunt placed in their head. This device will be monitored, and data recorded via hooking up the electrodes to a device called the Arduino (a small data recording device). Multiple data points will be collected about the new medical device performance, stability, flow capability, durability, etc. as the design is tweaked for the best possible version of a new medical device to be ultimately created and used in the field. Additionally, the CSF will be tested by collection via the catheter port and testing for potential ion presence to determine its impact on the device, as well as chart review for labs and demographics that may impact the new device.

Movement Disorder

Neurochemical and Neurophysiological Assessment During Surgery: Parkinson’s, Dystonia and Essential Tremor

PI: Mark Witcher, MD, PhD

Collaboration with Read Montague, PhD, Virginia Tech

One important issue for understanding diseases and disorders that involve dopaminergic systems, any system or disease that involves the dopamine neurotransmitter (like brain degenerative disorders like Parkinson’s), is to establish an undeniable link between the body’s internal events involved in reward processing and the ? (maybe not understanding correctly – Andy) negative disordered outcomes involved in disease that these events lead to. There is a large and growing body of knowledge concerning the molecular and cellular processes involved in reward pathways and the way in which they are influenced by drugs typically seen in abuse and neurological disorders. Despite the rapid progress in experimental methods for studying dopaminergic systems, there is still a large gap in our knowledge concerning the type of information processing mechanisms that these systems carry out. The broad objective of this proposal is to establish one such link by providing a computational working understanding of the kinds of information constructed and broadcasted by midbrain dopamine systems and the influence of these signals on their following neural targets.

This study will provide functional data concerning brain function and structure using active and passive reward-oriented tasks to uncover changes in the brain’s chemical activity while undergoing deep brain stimulator implantation surgery where electrodes are placed deep in the brain and stimulate the brain to basically rid itself of abnormal activity. Since much work in this system has been done in the intact human brain, the goal here is to understand the parts of the brain associated with higher order cognitive processes such as reward processing and decision-making, at both functional and structural levels. Some subjects may have the opportunity to participate in an fMRI study prior to this study using same or similar reward-oriented tasks. No prior fMRI study participation is required for the current proposed study. If subjects in the current study have also participated in a prior fMRI study, the results will be compared.

Additional Information

Studies on mesencephalic dopamine systems in behaving animals suggest that activity changes in dopamine neurons of the ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra represent computationally important signals, that is, dopamine fluctuations represent errors in predictions of the time and amount of future rewarding events (see Schultz et al. 1997 for review). These errors can be transmitted via changes in the spiking activity of the neurons and resultant fluctuations in dopamine (Montague and Sejnowski, 1994; Montague et al., 1996; Schultz et al., 1997; Montague et al., 2004; Bayer and Glimcher, 2004). Further changes in dopaminergic target structures have been found in humans using fMRI. Blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) responses measuring reward prediction error signals can be dissociated in the striatum according to whether an action is required for the acquisition of the reward. During active and passive tasks, the reward prediction error is evident in the ventral striatum (McClure et al., 2003, O'Doherty et al., 2003). In active tasks, however, a strong response in the dorsal striatum also appears (O'Doherty et al., 2003). Computational models also suggest that a decrease in dopamine in the system may result in delay times for reward decision making (Montague et al., 1996). It is therefore reasonable to suspect that the above computational interpretation of dopaminergic activity will yield novel insights into those aspects of reward processing and decision making over which dopamine has a strong influence.

Diseases and disorders that disrupt the dopaminergic system provide an opportunity to investigate this system in varying states of dysfunction. Parkinson's disease (PD) is characterized by progressive loss of nigro-striatal dopaminergic neurons (Mayeux, 2003). Dopamine depletion in the striatum results in motor deficits, such as akinesias, rigidity, and tremor. Dopamine depletion can also cause other nonmotor features such as depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment. Dopamine replacement treatment is common in Parkinson’s disease and reduces the motor deficits. Long-term treatment with L-dopa, the precursor to dopamine synthesis, can induce other motor deficits and motor fluctuations (Wichmann and DeLong, 2006).

Another form of treatment for certain PD patients is deep brain stimulation (DBS) to modify cortico-basal ganglia circuits. Stimulation electrodes are inserted into specific brain regions (globus pallidus, thalamus, subthalamic nucleus, or pedunculopontine nucleus) and high-frequency stimulation is delivered via an externally programmable pulse generator. This stimulation results in immediate effects on motor deficits and reduces the dose of medication needed to target other residual disease symptoms (Kringelbach et al.,2007). Indeed, the success of DBS for Parkinson's disease has led to its use in the treatment of other neurological and neuropsychiatric diseases, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, multiple sclerosis, Tourette’s syndrome, and chronic pain.

In the instance of Parkinson's disease, the best candidates for DBS are patients with levo-dopa responsive PD that have no psychiatric symptoms (Wichmann and DeLong, 2006). In this instance, DBS electrodes are implanted bilaterally, one hemisphere at a time. During implantation of the electrode, the neural activity surrounding the electrode sites is recorded to determine the location of the electrode in the brain. Sites such as the thalamus, subthalamic nucleus, and substantia nigra have specific neural activity patterns. Microelectrode mapping of these areas in response to passive and active movements is necessary to determine the upper and lower boundaries of the subthalamic nucleus to ensure proper placement of the electrode. After the electrode is positioned in the subthalamic nucleus, a brief neurological exam is performed to determine the proper generator settings for reduction in tremor and rigidity without concomitant alterations in motor and cognitive function. This procedure is repeated in the opposite hemisphere.

- Bayer HM, Glimcher PW. (2005) Midbrain dopamine neurons encode a quantitative reward prediction error signal. Neuron 47:129-41.

- Kringelbach ML, Jenkinson N, Owen SL, Aziz TZ. (2007) Translational principles of deep brain stimulation. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 623-35.

- Mayeux R. (2003) Epidemiology of neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci 26: 81-104.

- McClure SM, Berns GS, Montague PR. (2003) Temporal prediction errors in a passive learning task activate human striatum. Neuron 38: 339-46.

- Montague PR, Sejnowski TJ. (1994) The predictive brain: temporal coincidence and temporal order in synaptic learning mechanisms. Learn Mem 1: 1-33.

- Montague PR, Dayan P, Sejnowski TJ. (1996) A framework for mesencephalic dopamine systems based on predictive Hebbian learning. J Neurosci 16: 1936-47.

- Montague PR, McClure SM, Baldwin PR, Phillips PE, Budygin EA, Stuber GD, Kilpatrick MR, Wightman RM. (2004) Dynamic gain control of dopamine delivery in freely moving animals. J Neurosci 24: 1754-9.

- Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. (1997) A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 275: 1593-9.

- O'Doherty JP, Dayan P, Friston K, Critchley H, Dolan RJ. (2003) Temporal difference models and reward- related learning in the human brain. Neuron 38: 329-37.

- Wichmann T, Delong MR. (2006) Deep brain stimulation for neurologic and neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuron 52: 197-204

____________

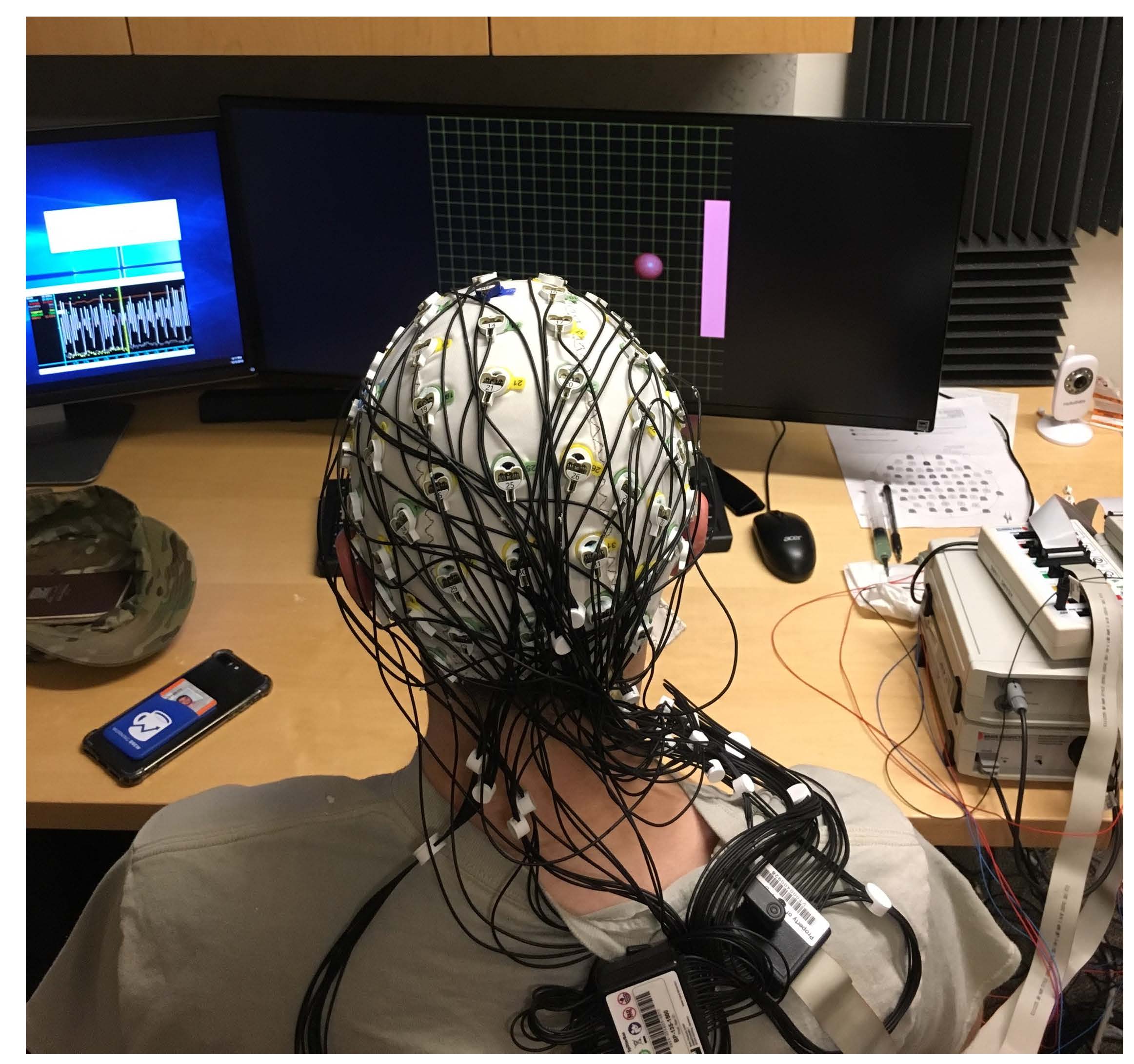

Neural Dynamics of Epilepsy Patients

PI: Mark Witcher, MD, PhD

Collaboration with Sujith Vijayan, PhD, Virginia Tech

This project will generate large datasets using intracranial electrodes, electrodes placed inside the skull usually at potential sites of seizure origin, implanted in patients with uncontrolled epilepsy to study the neural dynamics of the brain and what role sleep may have in motor learning, memory ordering and storage, responses to stimuli, and mental imagery. We additionally will investigate the neural activity in different behavioral states and sleep stages to better our understanding of the sleeping brains communication and organization of information for future use.

____________

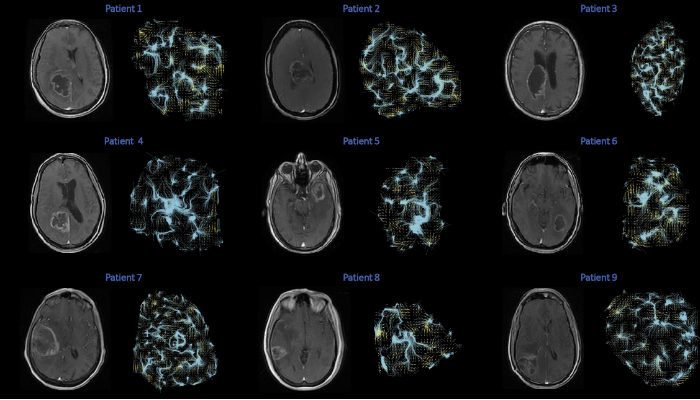

Electrochemical Measurements During Epilepsy Monitoring Procedures

PI: Mark Witcher, MD, PhD

Collaboration with Read Montague, PhD, Virginia Tech

Dysfunction in dopamine, serotonin, or norepinephrine associated brain signaling can result in a range of psychiatric conditions including depression, anxiety, chronic pain, addiction disorders, and problems with attention (attention deficit disorder) and arousal (narcolepsy). Despite the clear importance of these types of signaling systems and pathways, we know practically nothing about how these systems act in real-time (at sub-second timescales) in the human brain. The purpose of this research study is to gain basic knowledge about how the human brain works. Specifically, the goal of this study is to measure the levels of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine throughout the human brain and how these levels respond to reward in both passive and active situations. Subjects will consist of patients undergoing phase-II epilepsy monitoring. Functional MRI recordings will be carried out separately from the subject’s clinical stay if they consent to the optional portion of the study. A separate set of study tasks will be performed during fMRI scanning. Neurotransmitter recording will be carried out using clinical electrodes already implanted for epilepsy monitoring. Using refined techniques, we will be able to use recordings obtained from these electrodes to measure at sub-second resolution concentrations of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine all at the same time. Understanding the behavior of these neurotransmitters will have far reaching implications in the treatment of many psychiatric and neurological conditions.

Additional Information

This temporal resolution has proven to be important in basic research in rodent model organisms, where it has been shown that each of these neurotransmitters’ extracellular concentration changes within 100s of milliseconds of interacting with relevant stimuli while navigating moment-to-moment changes in the environment. Measurements with this kind of precision are necessary to be able to investigate how rapid changes in each of these signals modulate brain function, mood, and behavior in humans.

Currently, there is no technology available that will permit simultaneous sub-second measurements of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine in the human brain. However, the PI of this proposal (Montague) has recently developed a novel approach that enables real-time measurements of dopamine and serotonin using carbon fiber micro-sensors and a machine learning based approach to fast scan cyclic voltammetry (Kishida et al., 2011; Kishida et al., 2016; Moran et al., 2018). Further, preliminary evidence from the investigators’ lab suggests that this technology may be extended to simultaneously measure dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine in the human brain. Here, we propose to deploy a new recording protocol in combination with an FDA approved micro-sensor assembly (for epilepsy mapping) that combined will enable (for the first time ever) simultaneous measurements dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine micro-fluctuations with sub-second temporal resolution in the human brain. If successful, the proposed work could provide a significant technological advance for neuroscience research in human brain function and behavior, with potential translational impact in areas including in neurosurgery, neurology, and psychiatry.

Clinical context of proposed research: Patients with treatment (medication) resistant epilepsy can become candidates for surgical ablation of the epileptic foci. To determine which region of the brain is the source of the seizures patient undergo phase-I and if necessary phase-II epilepsy monitoring. Phase-I requires non-invasive electroencephalographic recordings using electrodes placed on the patient’s scalp. If these recordings are inconclusive, patient become candidates for intracranial depth electrode mapping, which requires brain surgery to place the depth electrodes (e.g., see Fig. 1) as shown in Fig. 2. An alternative depth electrode that is used for clinical purposes is AdTech’s “All-in-one Macro-Micro” electrode, where the micro contacts are radially spaced on the body of the depth electrode. These electrodes are FDA approved for standard-of-care use side-by-side with clinical research recordings. These electrodes and this procedure are the platform for the recordings we propose here. Importantly, we will only perform research recordings from sites that will necessarily be damaged by the clinical procedures, and due to the unknown epileptic foci will later be deemed either healthy or epileptic tissue.

Background to electrochemical measurement approach. The critical measurement approach that enables simultaneous electrochemical detection of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine is an electrochemical method called “fast scan cyclic voltammetry”. This approach has been utilized in rodents and rodent brain tissue for over 25 years. Briefly, a voltage is applied to a carbon fiber microelectrode. If this voltage is greater than or equal to the oxidation potential of a chemical species, then an electrochemical oxidation reaction takes place and the transfer of electrons (to the carbon fiber) is measured as a change in current. By quickly scanning over a range of applied potentials (e.g., -0.6V to +1.4V and back to -0.6V at a scan rate of 400V/s), a range of electrochemical currents can be detected. We have developed a machine learning based algorithm that allows us to infer the chemical species’ identity and concentration from this induced electrochemical spectrum. Tests like those shown in Figure 3 demonstrate that we can continuously monitor dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine micro-fluctuations with 100ms temporal resolution, which is orders of magnitude faster and with direct chemical specificity better that existing non-invasive measurement modalities like fMRI and PET and invasive approaches like microdialysis.

The macro-micro electrodes used will be identical to those utilized in previous IRB-approved procedures for epilepsy monitoring.

The clinical importance of investigating the action of the neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine is perhaps best highlighted by the pharmaceuticals used to treat major psychiatric conditions like depression, anxiety disorders, chronic pain, attention deficit disorders, and nicotine addiction. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are used to treat depression and anxiety; Norepinephrine and Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (NSRIs) are used to treat depression and chronic pain; Norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors are used to treat depression, attention deficit disorders, and have been used as an aid to smoking cessation; and Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) have been used to treat depression, narcolepsy, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, as an aid to weight loss, and anxiety disorders characterized by low arousal. Furthermore, abused substances (e.g., cocaine, nicotine, alcohol, and opiates) are known to alter the subtle balance between neurotransmitter release and reuptake in model organisms.

From a basic science perspective, we believe that dopamine is critical for reward processing and motivated behavior, serotonin for processing aversive stimuli and mood regulation, and norepinephrine for regulating states of arousal and attention. These neurotransmitters are released from neurons located in the brain stem (serotonin and norepinephrine) and midbrain (dopamine) whose axon terminals distribute and broadcast these signals throughout the brain including targets throughout the cortex (dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine), basal ganglia (dopamine and serotonin), hippocampus (dopamine and serotonin), and amygdala (dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine). While we know that these systems are critical, most of what we know comes from model organism research at timescales too slow to understand how rapid, real-time fluctuations in these signals contribute healthy human cognition, decision-making, and behavior. Additionally, very little is known about the neurophysiological processes involved in mindfulness. Recently, studies have established that subjects with experience in mindfulness shows attenuation of reward-related responses in ventral striatum (Kirk et al., 2019, 2015). In line with this finding is previous work demonstrating that changes in mental states, such as employing emotion regulation strategies, may regulate reward expectation (Delgado et al., 2008; Gu et al., 2014). This proposal allows us to examine to which degree training in mindfulness will lead to changes both behaviorally and in the underlying neurochemistry.

We also have a very limited understanding of how dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine systems interact. In any given brain region, it may be expected that there are one, two, or all three of these neurotransmitter systems contributing to the local neural information processing. In the human brain (and non-human primate brain) we know little about how the density of release sites or the dynamics of release change with psychiatric conditions or the medications used to treat them. This lack of knowledge does not stem from a lack of interest in the neuroscience, neurology, psychiatry, or neurosurgery disciplines; rather, the necessary technology and research paradigm has not been available. This proposal seeks to take the first steps in developing novel hardware (micro-sensor assembly) and pair it with the PI’s machine learning based approach to fast scan cyclic voltammetry to simultaneously measure continuous sub-second microfluctuations of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine in the human brain.

Simultaneous sub-second measurements of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine in the human brain would allow investigators to monitor how these three neurotransmitters fluctuate in real-time. Such technology could potentially be used to develop real-time biomarkers of dynamic brain activity in disease specific brain areas, which may be used diagnostically or prognostically in psychiatry (e.g., depression or OCD) and neurology (e.g., Parkinson’s disease or epilepsy) and neurosurgery (e.g., deep brain stimulation electrode placement or lesion/tumor resection boundaries). Further, such measurements could be used to assess exactly how drugs (clinical treatments or abused substances) alter the function of these neuromodulatory systems in real-time in the human brain. Finally, such technology could provide a breakthrough in intracranial neuroscience research into the basic neural mechanisms underlying decision-making processes that may generally be affected in humans prone to poor health-related behaviors.

The questionnaires and assessments proposed will provide insights into disorders (and anxiety, depression) and psychological status that we hope to understand in relation to the neurochemistry measures. They will also provide baseline information that may be used to characterize and group the population to further refine our understanding of the neural responses.

References

- http://adtechmedical.com/depth-electrodes

- http://www.epilepsy.com/

- *Moran, R.J., *Kishida, K.T., *Lohrenz, T., Saez, I.G., Laxton, A.W., Witcher, M., Tatter, S., Elllis, T.L., Phillips, P.E.M., Dayan, P., and Montague, P.R. (2018) The protective action encoding of serotonin transients in the human brain. Neuropsychopharamcology, 43: 1425-1435. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.304

- Kishida, K.T., Saez, I.G., Lohrenz, T., Witcher, M., Laxton, A., Tatter, S., White, J.P., Elllis, T.L., Phillips, P.E.M., and Montague, P.R., (2016). Sub-second dopamine fluctuations in human striatum encode superposed error signals about actual and counterfactual reward. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A. 113(1): 200-205. doi:10.1073/pnas.1513619112. PMID: 26598677.

- *Kishida, K.T., *Sandberg, S.S., Lohrenz, T., Comair, Y.G., Saez, I.G., Phillips, P.E.M., and Montague, P.R. (2011). Sub-Second Dopamine Detection in Human Striatum. PLoS ONE. 6(8): e23291. PMID: 21829726.

- Gu X, Kirk U, Lohrenz TM, Montague PR. Cognitive strategies regulate fictive,

but not reward prediction error signals in a sequential investment task. Hum

Brain Mapp. 2014 Aug;35(8):3738-49. - Kirk U, Montague PR. Mindfulness meditation modulates reward prediction errors

in a passive conditioning task. Front Psychol. 2015 Feb 12;6:90. - Kirk U, Pagnoni G, Hétu S, Montague R. Short-term mindfulness practice

attenuates reward prediction errors signals in the brain. Sci Rep. 2019 May

6;9(1):6964. - Delgado MR, Gillis MM, Phelps EA. Regulating the expectation of reward via

cognitive strategies. Nat Neurosci. 2008 Aug;11(8):880-1.

Pain

DePuy Synthes Spine Clinical Registry (CONDUIT™ Interbody Platform /EIT Cellular Titanium®)

PI: Gregory Howes, DO

Spinal fusion, basically re-joining spinal bones, is often a solution for patients experiencing chronic back or neck pain. Spinal fusion is a surgical procedure where two or more vertebrae are combined to form one continuous bone by removing damaged or deficient discs between the two vertebrae. The goal of spinal fusion surgery is to kickstart bone growth between two or more vertebrae using replacement synthetic or cadaver collected bone and a spacer in the intervertebral space. Once new bone forms, the vertebrae will be linked together, and there should be no further movement between the fused segments, which is what contributed to the patient’s pain. This study’s goal is to review patient’s experience in pain relief, device effectiveness, complications, and radiographic (imaging) findings of the CONDUIT™ Interbody Platform /EIT Cellular Titanium in a post market analysis being conducted at the behest of DePuy Synthes Spine.

For more information please see: Neurosurgery Research | Carilion Clinic

____________

Investigation of Low-Intensity Focused Ultrasound for the Control of Chronic Low Back Pain

PI: Mark Witcher, MD, PhD

Collaboration with Wynn Legon, PhD, Virginia Tech

Chronic pain is a major public health problem. An estimated 100 million Americans have experienced chronic pain leading to significant economic and social burden. The estimated annual cost of managing chronic pain in the United States is as high as $635 billion per year. Pharmacological treatments frequently require the use of addictive pain-killing opioids resulting in a major epidemic of abuse in the United States. New, non-addictive treatments for pain are needed. Neuromodulation, or the alteration of nerve activity with targeted electrical signals, with low intensity focused ultrasound (LIFU) may provide a non-pharmacological treatment. The enormous potential of LIFU stems from the ability to focus ultrasound through the intact skull to a very specific and precise target spot size anywhere in the brain. This makes it a powerful alternative to both invasive neurosurgical procedures and other noninvasive brain stimulation techniques. The anterior insula (AI) and the posterior insula (PI) are promising targets to treat chronic pain. Multiple lines of evidence support the involvement of the dorsal anterior insula in the intensity of the pain while the posterior insula is thought to signal the affective or emotional response from the pain to the brain which guides behavioral response to the pain. Shutting or slowing down either of these regions may serve to reduce the overall pain experience. Unfortunately, both areas lie deep to the cortical surface of the brain preventing access using conventional noninvasive techniques like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial electric stimulation (TES) that have poor accuracy and lack depth penetration. It is the purpose of this proposal to investigate the influence of neuromodulation with LIFU to either the AI or PI on distinct aspects of the pain experience (intensity and emotional response) in patients waiting to receive a dorsal column stimulator (DCS) for chronic pain, a standard of care treatment of chronic low back and radicular pain. It is the long-term goal of this project to advance LIFU as a human pain management tool to enhance the health and reduce suffering in those with chronic pain.

Additional Information

LIFU for spatially-targeted neuromodulation. LIFU is a novel neuromodulatory approach which uses mechanical energy to non-destructively and reversibly modulate neuronal activity with high spatial resolution and adjustable depth of focus 1–7. LIFU has been used safely and effectively for cortical and sub-cortical neuromodulation in mouse 8–12, rat 13–16, rabbit17, sheep18,19, pig20 and primate21-26. It is also an effective method of transient cortical and sub-cortical neuromodulation in humans1,2,27-35.

Human LIFU. We have extensive experience testing LIFU for cortical and sub-cortical neuromodulation in humans1,2,27,34,36-39. We precisely targeted the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) in humans and attenuated somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs) generated in the posterior bank of the central sulcus 1. Additionally, LIFU altered tactile sensitivity as compared to sham stimulation. Movement of the transducer by one centimeter removed the effect - validating the spatial specificity of the neuromodulation. Subsequent work showed that LIFU can alter EEG dynamics34. We have also used LIFU to modulate the primary motor cortex (M1)27. We further defined the spatial resolution of LIFU with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI38,39. We have also shown that LIFU is effective for deep brain neuromodulation in humans. We MRI-targeted the ipsilateral thalamus and found LIFU to significantly reduced the amplitude of the P14 SEP generated in VPL of thalamus2.

LIFU mechanisms of action. The mechanism of LIFU is likely due to tissue at the focus point absorbing energy and moving along the direction of the beam. Focused beams cause a distortion of the tissue with subsequent strain that can activate stretch sensitive ion channels causing neurotransmitter release40–43. Kubanek et al. demonstrated mechanosensitive receptors are necessary for ultrasound-elicited behavior in C. elegans44. The expression of Piezo1, a mechanosensitive ion channel, in mammalian cells, but not NaV1.2, imparts ultrasound sensitivity41. The mechanosensitive ion channels TREK-1, TREK-2, TRAAK, and NaV1.5 have all been demonstrated to be activated by ultrasound43,44.

LIFU safety. Ultrasound for neuromodulation follows the safety guidelines of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for obstetric diagnostic applications45. The FDA guidelines include derated limits of spatial peak pulse average intensity (ISPPA) of 190 W/cm2, ISPTA of 720 mW/cm2 and a mechanical index (MI = peak negative pressure/ frequency) of 1.9. There are numerous reports on the safety of ultrasound for neuromodulation in small animal9–11,46,47. In a large animal, Dallapiazza looked at hematoxylin and eosin stains of targeted brain regions and did not find any irregularities20. Gaur et al. (2020) found no red blood cell engulfment, no hemosiderin-laden macrophages, no neuronal necrosis and no apoptosis and the examined sections were negative for apoptosis48. In macaques, they found no evidence for any tissue damage at intensities up to 25.8 W/cm2 ISPTA (> 4x what we propose to use here)48. In humans, Stern et al. (2021)49 found no detectable damage using histology at intensities of 5760 mW/cm2 ISPTA that is 8x what we propose. We recently compiled a report of LIFU in humans and found no serious adverse events and a safety profile similar to TMS and TES36.

- Legon, W. et al. Transcranial focused ultrasound modulates the activity of primary somatosensory cortex in humans. Nature neuroscience 17, 322–329 (2014).

- Legon, W., Ai, L., Bansal, P. & Mueller, J. K. Neuromodulation with single element transcranial focused ultrasound in human thalamus. Human brain mapping 39, 1995–2006 (2018).

- Darmani, G. et al. Non-invasive transcranial ultrasound stimulation for neuromodulation. Clinical Neurophysiology (2021).

- Blackmore, J., Shrivastava, S., Sallet, J., Butler, C. R. & Cleveland, R. O. Ultrasound Neuromodulation: A Review of Results, Mechanisms and Safety. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 45, 1509–1536 (2019).

- Bystritsky, A. & Korb, A. S. A Review of Low-Intensity Transcranial Focused Ultrasound for Clinical Applications. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep 2, 60–66 (2015).

- Sassaroli, E. & Vykhodtseva, N. Acoustic neuromodulation from a basic science prospective. J Ther Ultrasound 4, 17 (2016).

- Naor, O., Krupa, S. & Shoham, S. Ultrasonic neuromodulation. J. Neural Eng. 13, 031003 (2016).

- Kamimura, H. et al. Ipsi- and Contralateral Motor Response Using Ultrasound-induced Neurostimulation in Deeply Anesthetized Mice. Physics Procedia 70, 1212–1215 (2015).

- Kamimura, H. A. S. et al. Focused ultrasound neuromodulation of cortical and subcortical brain structures using 1.9 MHz: FUS neuromodulation of cortical/subcortical brain structures. Med. Phys. 43, 5730–5735 (2016).

- Tufail, Y. et al. Transcranial Pulsed Ultrasound Stimulates Intact Brain Circuits. Neuron 66, 681–694 (2010).

- Mehi , E. et al. Increased Anatomical Specificity of Neuromodulation via Modulated Focused Ultrasound. PLoS ONE 9, e86939 (2014).

- King, R. L., Brown, J. R., Newsome, W. T. & Pauly, K. B. Effective Parameters for Ultrasound-Induced In Vivo Neurostimulation. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 39, 312–331 (2013).

- Kim, H., Chiu, A., Lee, S. D., Fischer, K. & Yoo, S.-S. Focused Ultrasound-mediated Non-invasive Brain Stimulation: Examination of Sonication Parameters. Brain Stimulation 7, 748–756 (2014).

- Yu, K., Niu, X., Krook-Magnuson, E. & He, B. Intrinsic functional neuron-type selectivity of transcranial focused ultrasound neuromodulation. Nat Commun 12, 2519 (2021).

- Sharabi, S. et al. Non-thermal focused ultrasound induced reversible reduction of essential tremor in a rat model. Brain Stimulation 12, 1–8 (2019).

- Yang, P. S. et al. Transcranial Focused Ultrasound to the Thalamus Is Associated with Reduced Extracellular GABA Levels in Rats. Neuropsychobiology 65, 153–160 (2012).

- Yoo, S.-S. et al. Focused ultrasound modulates region-specific brain activity. NeuroImage 56, 1267–1275 (2011).

- Yoon, K. et al. Effects of sonication parameters on transcranial focused ultrasound brain stimulation in an ovine model. PLoS ONE 14, e0224311 (2019).

- Lee, W. et al. Image-Guided Focused Ultrasound-Mediated Regional Brain Stimulation in Sheep. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 42, 459–470 (2016).

- Dallapiazza, R. F. et al. Noninvasive neuromodulation and thalamic mapping with low-intensity focused ultrasound. Journal of Neurosurgery 128, 875–884 (2018).

- Verhagen, L. et al. Offline impact of transcranial focused ultrasound on cortical activation in primates. eLife 8, e40541 (2019).

- Folloni, D. et al. Manipulation of Subcortical and Deep Cortical Activity in the Primate Brain Using Transcranial Focused Ultrasound Stimulation. Neuron 101, 1109-1116.e5 (2019).

- Kubanek, J. et al. Remote, brain region–specific control of choice behavior with ultrasonic waves. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz4193 (2020).

- Deffieux, T. et al. Low-Intensity Focused Ultrasound Modulates Monkey Visuomotor Behavior. Current Biology 23, 2430–2433 (2013).

- Wattiez, N. et al. Transcranial ultrasonic stimulation modulates single-neuron discharge in macaques performing an antisaccade task. Brain Stimulation 10, 1024–1031 (2017).

- Yang, P.-F. et al. Neuromodulation of sensory networks in monkey brain by focused ultrasound with MRI guidance and detection. Sci Rep 8, 7993 (2018).

- Legon, W., Bansal, P., Tyshynsky, R., Ai, L. & Mueller, J. K. Transcranial focused ultrasound neuromodulation of the human primary motor cortex. Scientific reports 8, 1–14 (2018).

- Lee, W. et al. Image-Guided Transcranial Focused Ultrasound Stimulates Human Primary Somatosensory Cortex. Sci Rep 5, 8743 (2015).

- Lee, W. et al. Transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation of human primary visual cortex. Sci Rep 6, 34026 (2016).

- Monti, M. M., Schnakers, C., Korb, A. S., Bystritsky, A. & Vespa, P. M. Non-Invasive Ultrasonic Thalamic Stimulation in Disorders of Consciousness after Severe Brain Injury: A First-in-Man Report. Brain Stimulation 9, 940–941 (2016).

- Cain, J. A. et al. Real time and delayed effects of subcortical low intensity focused ultrasound. Sci Rep 11, 6100 (2021).

- Beisteiner, R. et al. Transcranial Pulse Stimulation with Ultrasound in Alzheimer’s Disease—A New Navigated Focal Brain Therapy. Adv. Sci. 7, 1902583 (2020).

- Fomenko, A. et al. Systematic examination of low-intensity ultrasound parameters on human motor cortex excitability and behavior. eLife 9, e54497 (2020).

- Mueller, J., Legon, W., Opitz, A., Sato, T. F. & Tyler, W. J. Transcranial focused ultrasound modulates intrinsic and evoked EEG dynamics. Brain stimulation 7, 900–908 (2014).

- Sanguinetti, J. L. et al. Transcranial Focused Ultrasound to the Right Prefrontal Cortex Improves Mood and Alters Functional Connectivity in Humans. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 52 (2020).

- Legon, W. et al. A retrospective qualitative report of symptoms and safety from transcranial focused ultrasound for neuromodulation in humans. Scientific reports 10, 1–10 (2020).

- Legon, W., Rowlands, A., Opitz, A., Sato, T. F. & Tyler, W. J. Pulsed ultrasound differentially stimulates somatosensory circuits in humans as indicated by EEG and FMRI. PloS one 7, e51177 (2012).

- Ai, L., Mueller, J. K., Grant, A., Eryaman, Y. & Legon, W. Transcranial focused ultrasound for BOLD fMRI signal modulation in humans. in 1758–1761 (IEEE, 2016).

- Ai, L., Bansal, P., Mueller, J. K. & Legon, W. Effects of transcranial focused ultrasound on human primary motor cortex using 7T fMRI: a pilot study. BMC Neurosci 19, 56 (2018).

- Tyler, W. J. The mechanobiology of brain function. Nat Rev Neurosci 13, 867–878 (2012).

- Prieto, M. L., Firouzi, K., Khuri-Yakub, B. T. & Maduke, M. Activation of Piezo1 but Not NaV1.2 Channels by Ultrasound at 43 MHz. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 44, 1217–1232 (2018).

- Kubanek, J. et al. Ultrasound modulates ion channel currents. Sci Rep 6, 24170 (2016).

- Sorum, B., Rietmeijer, R. A., Gopakumar, K., Adesnik, H. & Brohawn, S. G. Ultrasound activates mechanosensitive TRAAK K + channels through the lipid membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118, e2006980118 (2021).

- Kubanek, J., Shukla, P., Das, A., Baccus, S. A. & Goodman, M. B. Ultrasound Elicits Behavioral Responses through Mechanical Effects on Neurons and Ion Channels in a Simple Nervous System. J. Neurosci. 38, 3081–3091 (2018).

- Health, C. for D. and R. Marketing Clearance of Diagnostic Ultrasound Systems and Transducers. U.S. Food and Drug Administration https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/marketing-clearance-diagnostic-ultrasound-systems-and-transducers (2019).

- Burks, S. R. et al. Investigation of Cellular and Molecular Responses to Pulsed Focused Ultrasound in a Mouse Model. PLOS ONE 6, e24730 (2011).

- Bystritsky, A. et al. A review of low-intensity focused ultrasound pulsation. Brain Stimulation 4, 125–136 (2011).

- Gaur, P. et al. Histologic safety of transcranial focused ultrasound neuromodulation and magnetic resonance acoustic radiation force imaging in rhesus macaques and sheep. Brain Stimulation 13, 804–814 (2020).

- Stern, J. M. et al. Safety of focused ultrasound neuromodulation in humans with temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Stimulation 14, 1022–1031 (2021).

- Wager, T. D. et al. An fMRI-Based Neurologic Signature of Physical Pain. N Engl J Med 368, 1388–1397 (2013).

Traumatic Injury

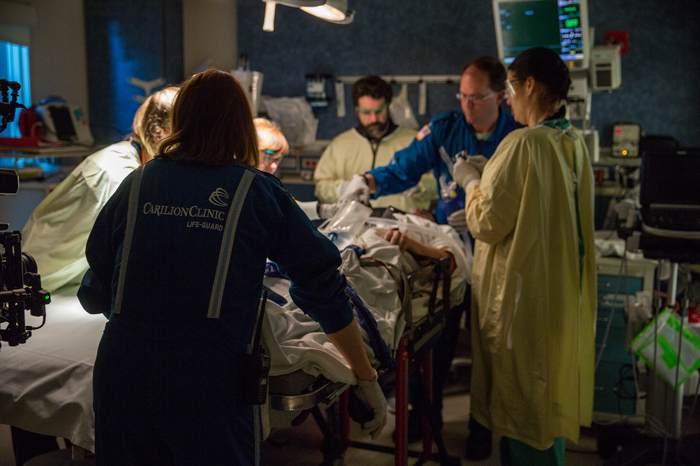

Neurovascular Markers and Inflammatory Predictors in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

PI: Eric Marvin, DO

Collaboration with Michelle Theus, PhD; and Alicia Pickrell, PhD, Virginia Tech

TBI (traumatic brain injury) affects millions of patients annually, with the most cases being in children, young adults, the elderly, and active-duty military members. Despite how common it is and its ability to cause long-term health problems, our current treatments for TBI are very limited. By gaining a better understanding of the inflammatory (swelling) effects of TBI on the brain, we may identify possible therapeutic targets to reduce inflammation in the brain and cell death after injury. Antiviral drugs and FDA approved compounds that target antiviral proteins in the body called interferons in autoimmune disorders may be able to help TBI patients. Moreover, findings from our study may reveal a new protective marker present in the immune cells of juvenile patients that may be able to be used for therapeutic intervention in adult and aged patients.

In this study, we will study the genetic profile of whole blood and examine whether a virally induced interferon release occurs in humans after TBI. We hypothesize that TBI induces a genetic marker or sign in immune cells induced by circulating interferons in the blood serum of patients after injury depending on the age of the patient.

Additional Information

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects 5.3 million Americans and is a leading cause of death and disability; yet, relatively little progress has been made in alleviating neurodegeneration after the initial incident. Inflammation is a key contributor to neuronal death post-injury. When immune cells detect damaged or infected tissue, the Type I interferon response recruits other immune cells. While an inflammatory response is important for clearing damaged tissue debris and infections, sustained inflammation in the brain is harmful. We found that a virally induced interferon response occurs acutely after injury, and genetically knocking out this response in a preclinical model of TBI is protective. Moreover, it is unclear whether this response and the overall transcriptomic response is age dependent. Therefore, our goal is to collect whole blood and evaluate the immune cell genetic profile and interferon presence in pre-adolescent (5-10 years) and adult aged (18-50) male and females human patients following moderate and severe TBI.

We will determine the gene profile of whole blood and interferon/protein expression using serum from patients (5-10 yrs old vs 18-50 yrs old) collected as part of standard care/treatment, usually on at arrival 0-24 hrs (two tubes) and at 48-hrs and 72-hrs (one tube each) post admittance. We will purchase samples for control patients from the University of Virginia repository or commercial sources such as Zenbio. (In order to detect a statistically significant difference in the correlation (if one exists) between age and the absolute value of the interferons at 5% level of significance, 80% power, and small effect size, this study will need 96 patients in eachgroup (children and adults). This will include 96 control adult sera and 96 control child sera to reach statistical significance (total of 192 sera).

The amount or absolute values for inflammatory cytokines; Blood brain barrier junctional proteins; Akap12, and vascular growth or vascular damage factors (all important in the inflammatory cascade process that is triggered in head trauma) will be tested using assays and ELISAs in the laboratory of Dr. Pickrell. Follow-up questionnaires will occur at 1, 3, 6 months and 12 months after discharge as an over the phone follow-up: Glasgow outcome scale (GOS).

Our pre-clinical findings suggest EphA4 is strongly upregulated in the adult brain and blood after TBI. This molecule contributes to tissue damage and prevent the positive effects of Tie2. We also find that younger, pre-adolescent animals are able to suppress EphA4 and prevent progressive damage. When monocytes that lack EphA4 or are from young mice, are transferred to injured adult mice we also find protection after TBI. These studies will confirm our findings in human subjects and help determine if this information can be used for biomarker testing or therapeutics. (EphA4 is a receptor tyrosine kinase that blocks AKT signaling downstream of Tie2 (another tyrosine kinase receptor) to regulate pro-inflammatory polarization state of immune cells. Tie2-expressing monocytes are pro-resolving and are advantageous in injury. Therefore, suppressing or preventing EphA4 activation will improve this pathway, we predict in humans. We do not plan to test integrin and have not mentioned this interaction.

____________

Multi-Modal Biomarkers as Predictors of Post-Traumatic Epilepsy (PTE) and Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) after Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

PI: Eric Marvin, DO

Collaboration with Michelle Theus, PhD, Virginia Tech

This study aims to determine the relationship between brain blood vessel and brain immune system biomarkers of patients diagnosed with post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE) or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) after traumatic brain injury (TBI) and clinical outcomes. Identifying potential correlations could provide insight into how PTE and MCI develop after TBI and suggest potential pathways for new treatments and clinical management. We will have three participant groups: TBI with PTE, TBI with MCI, and TBI controls. Patients will be recruited for collection of blood samples, as well as some surveys. After collection, samples will be processed for identification of brain blood vessel and immune system biomarkers. Chart review will be conducted for features related to each patient’s demographics, epilepsy, and TBI. All data will be stored in RedCAP and analyzed on SPARC to determine the association between biomarker expression and PTE and biomarker expression and MCI after TBI.

Additional Information

The public health burden of traumatic brain injury (TBI) is substantial, affecting the lives of millions nationwide. Importantly it affects all sex and age groups. A recent report to congress on TBI led to several recommendations for addressing critical gaps. While prevention of TBI is the key public health strategy for reducing the burden, it is imperative for those in public health, clinical practice, and research to design and evaluate effective rehabilitation strategies that reduce the negative health effects of TBI. The report addressed a need for strategies to tackle the short and long-term consequences of head injury. One hallmark of both acute and chronic TBI is neuroinflammation, a known causative agent in the progressive onset of chronic conditions, namely neurodegeneration, post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE), and mental health (PTSD/sleep). Our interdisciplinary approach capitalizes on a focused team aimed at developing common data sets to identify links between neuroimmunology, imaging, PTE, and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) after TBI.

MCI is a common consequence of TBI that is associated with poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL) scores in physical, social role and emotional functioning, and mental health domains (1). The pathophysiology of MCI after a brain injury is not well understood, but it is associated with a higher risk of further cognitive decline such as Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias (2).

PTE is the development of recurring seizures subsequent to a TBI. PTE accounts for 20% of all epilepsy cases and most commonly affects younger patients (3-5). Most affected patients experience generalized or focal seizures with secondary generalization (6,7). The mechanisms of PTE development are unclear, and there is no known strategy to prevent their onset (8).

To our knowledge, there are no combined clinical-biomarker prognostic models to predict outcomes and progression of PTE or MCI after TBI. Therefore, it is essential to determine the pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets to prevent their onset or progression.

References

1. Gorgoraptis, N., Zaw-Linn, J., Feeney, C., Tenorio-Jimenez, C., Niemi, M., Malik, A., Ham, T., Goldstone, A. P., & Sharp, D. J. (2019). Cognitive impairment and health-related quality of life following traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation, 44(3), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.3233/nre-182618

2. LoBue C, Denney D, Hynan LS, Rossetti HC, Lacritz LH, Hart J, Womack KB, Woon FL, Cullum CM. Self-Reported Traumatic Brain Injury and Mild Cognitive Impairment: Increased Risk and Earlier Age of Diagnosis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51(3):727-36. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150895. PMID: 26890760; PMCID: PMC4853649.

3. Annegers JF, Coan SP. The risks of epilepsy after traumatic brain injury. Seizure. 2000;9(7):453-457. doi:10.1053/seiz.2000.0458

4. Jennett B. Trauma as a Cause of Epilepsy in Childhood. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2008;15(1):56-62. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1973.tb04866.x

5. Semah F, Picot MC, Adam C, et al. Is the underlying cause of epilepsy a major prognostic factor for recurrence? Neurology. 1998;51(5):1256-1262. doi:10.1212/WNL.51.5.1256

6. Haltiner AM, Temkin NR, Dikmen SS. Risk of seizure recurrence after the first late posttraumatic seizure. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1997;78(8):835-840. doi:10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90196-9

7. Englander J, Bushnik T, Duong TT, et al. Analyzing risk factors for late posttraumatic seizures: A prospective, multicenter investigation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2003;84(3):365-373. doi:10.1053/apmr.2003.50022

8. Agrawal A, Timothy J, Pandit L, Manju M. Post-traumatic epilepsy: An overview. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2006;108(5):433-439. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.09.001

____________

Predictive Markers for Recovery in CSF of Spinal Cord Injury Patients

PI: Adeolu Olasunkanmi, MD

Collaboration with Pam VandeVord, PhD, Virginia Tech

Spinal cord injury is a complicated and devastating neurological disease. Initial primary injury is often worsened by the bodies’ natural recovery systems due to the reckless nature of some healing responses causing a dangerous cycle of secondary, and further, injuries, such as large bleeds, blood clots, constriction of important blood vessels, stroke, and swelling on the spinal cord (1). The occurrence of these secondary injuries worsen the initial trauma injury with additional and growing damage to nearby spinal cord tissue leading to further cell death of neurons and their protective cells, the movement of harmful inflammatory cells to the area, as well as the condition, astrocytosis which limits secondary injury but also slows the regeneration of new healthy neurons (1). Indeed, spinal cord injury is a major cause of long-term physical impairment or disability in the United States with a new-case rate of approximately 54 cases per one million persons or 17,700 cases annually (2). Moreover, the present number of cases of spinal cord injury in the United States is 288,000 persons (2). Current treatments are limited to early surgical intervention, strict blood pressure control, and basic supportive measures. In recent years, numerous studies have begun to investigate the important biological processes negatively impacted by spinal cord injury in order to develop novel therapeutics to target the specific molecules involved in those processes that may be able to prevent secondary injury. However, the majority of these potential molecular targets have only been identified in animal models (2). To our knowledge, no study to date has investigated human cerebrospinal fluid or genetic biological markers at different time points in patients with various types of trauma-related spinal cord injuries. The primary aim of the present study is to evaluate cerebrospinal fluid inflammatory profiles and genetic markers in patients with various types of acute spinal cord injury in order to predict degree of potential harm to the nervous system as well as identify theoretical molecular targets for new therapeutic medications.

In conjunction with the collection of cerebrospinal fluid for analysis, a secondary aim of the present study is to evaluate the effectiveness of draining cerebrospinal fluid for a total of 72 hours on the healing of the neurologic injury. Prior studies have supported the use of cerebrospinal fluid draining as an additional preventative intervention of lower body paralysis in patients undergoing a type of spinal cord injury-related aneurysm’s corrective surgery (6). Indeed, animal studies evaluating the use of cerebrospinal fluid draining have reported 12% of patients developing lower limb neurologic deficits who underwent cerebrospinal fluid draining compared to 33% of control subjects (without cerebrospinal fluid draining) during this surgery.

In the present study, we will gain these data and implement cerebrospinal fluid drainage in order to keep intrathecal pressure at a goal of 10mm Hg at all times. As such, placement of a lumbar (lower spine) drain will serve a dual purpose. First, it will serve as a way where cerebrospinal fluid can be collected without repeated lumbar punctures over the course of 72 hours. Second, it will allow for cerebrospinal fluid drainage to keep pressures low to assess for neurologic improvement.

____________

Retrospective Study of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury

PI: Adeolu Olasunkanmi, MD

Spinal cord injury is a complicated and devastating neurological disease. Initial primary injury is expanded by ongoing pathologic disruption causing secondary damage, such as hemorrhage, intravascular thrombosis, vasospasm, ischemia, and spinal cord edema (1). Cascades of secondary injury expand the initial injury with progressive damage to adjacent tissue fostering further neuronal and glial death, migration and proliferation of reactive inflammatory cells, as well as reactive astrocytosis, which diminishes the expanse of secondary injury but simultaneously inhibits axonal regeneration (1). Indeed, spinal cord injury represents a major cause of long-term physical impairment in the United States with an incidence of approximately 54 cases per one million persons or 17,700 cases annually (2). Moreover, the prevalence of spinal cord injury in the United States is 288,000 persons (2). Current treatments are limited consisting of early surgical decompression and stabilization, strict blood pressure control, and supportive measures. In recent years, numerous studies have begun to investigate the molecular pathophysiology of spinal cord injury in order to develop novel therapeutics to target molecular mediators of secondary injury. However, the majority of these potential molecular targets have been identified in animal models (2). To our knowledge, no study to date has investigated cerebrospinal fluid inflammatory profiles or genetic markers at several time points in patients with various types of acute spinal cord injury with a multivariate analysis. The aim of the retrospective study is to evaluate instance of traumatic spinal cord injury and neurological outcomes at follow up as a control for our proposed prospective study to investigate cerebrospinal fluid inflammatory profiles and genetic markers in patients with various types of acute spinal cord injury.

A retrospective study will be implemented where charts will be reviewed from January 1 2014 – September 1, 2024 for all traumatic spinal cord injury patients The subject population will consist of all male and females indiscriminate of race or ethnicity, who are admitted to Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital for acute spinal cord injury of cervical or thoracic spine.

Vascular

Interrogating Human Serum Expression of EphA4 and Collateral Vessel Function Following Acute Ischemic Stroke

PI: Biraj Patel, MD

Collaboration with Michelle Theus, PhD, Virginia Tech

Stroke is the fifth leading cause of death and represents one of the leading causes of permanent neurological disability in the United States, afflicting nearly 800,000 people annually. To date, there are no safe and effective therapies to promote brain tissue stability and recovery. The current proposal seeks to extend novel pre-clinical animal findings into human clinical studies by evaluating specialized vessels in the brain called collaterals. Collateral vessels are natural “bypass” vessels that exist in our brain which lie dormant but following blockage of a major artery they act as alternative routes for blood to travel through which helps maintain flow of oxygen and nutrients. Patients with good collateral function recover better than those with poor function, however, the reason for this difference remains unknown. Our rodent studies indicate EphA4 receptor can prevent collateral growth and its release into the circulation may be a biomarker or sign of collateral function after stroke. This proposal will compare the serum levels of EphA4 with patient collateral scores on CT and other conventional techniques to view blood flow, as well as tissue damage using CT perfusion to view the circulation of blood in the brain (when applicable). These findings will improve our understanding of patient collateral plasticity and provide evidence for targeting EphA4 for predictive and therapeutic interventions.

Although improvements in wide-spread community awareness regarding the symptoms of stroke (ex/BE-FAST; balance, eyes, face, arm, speech and time) have prompted more rapid hospital admittance, close to half of all patients either do not arrive within 3 hours for tPA therapy which must be used early for success or they present with large vessel blockages for which tPA is ineffective. Recently, with the advent of endovascular therapy (ex/ clot removal using endovascular mechanical embolectomy or surgically removing endovascular blood clots), tissue protection can be achieved beyond the traditional 3-hour best treatment window and up to 24 hours post-symptom onset [4, 5]. The cerebral collateral circulation represents a powerful determinant of ischemic stroke outcome and enhancing this response through collateral therapeutics is under intense investigation. Moreover, it remains unclear why greater collateral function exists in some patients compared to others.

Additional Information

Our extensive pre-clinical findings in rodents show that vessel surface level cell-specific genetic Deletion of EphA4 receptor tyrosine kinase improves collateral function, enhances cerebral blood flow and provides protection against stroke within 24-hours. We also show that continuous, systemic delivery of EphA4 peptide inhibitor KYL EphA4 specifically can be found in EV released from cultured cells. The current proposal seeks 1-year support to test serum and serum-derived exosome for the presence of EphA4 in patients following stroke compared to control patients using human EphA4 ELISA kit (MyBioSource, Inc). These levels of EphA4 will be correlated with each patient collateral score using CT and conventional angiography using appropriate statistical analysis. We predict to find the highest levels of EphA4 in the serum of patients with least collateral function which will correlate with greater tissue damage. Levels of Angiopoeitin-1 and Angiopoeitin-2 will also be measured via ELISA to determine protein expression. This project focuses on identification of protein expression via ELISA without genetic analysis.

____________

Stroke Thromboembolism Registry of Imaging and Pathology (STRIP)

PI: Biraj Patel, MD

With the advent of mechanical thrombectomy, a novel surgical technique in which blood clots are removed by going directly through the blood vessels with thin tubes, for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke, there has been growing interest in the cellular and imaging characteristics of retrieved thromboemboli, resected blood clot tissues. Prior studies have suggested that studying clot composition can 1) provide insights into stroke causal factors and risk factors and 2) demonstrate blood flow restoration success with intravenous thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy. Furthermore, with improved characterization of clot composition regarding imaging and histopathologic features, it is possible that the imaging characteristics of a clot could help in device selection prior to the mechanical thrombectomy procedure itself. The goal of this study is to evaluate the clots that are extracted from a patient's brain during a stroke. Specifically, looking at what the clot is made up of and how it related to the ease of extraction, imaging, and patient outcome.

____________

Elucidating potential role and dynamics of cellular transmembrane protein expression in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients and associations with symptomatic vasospasm

PI: Kristine Ravina, MD

Collaboration with Scott Johnstone, PhD, Virginia Tech

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) induced vasospasm carries high risk of delayed cerebral ischemia in about 30% of patients that can potentially lead to neurologic deficits, permanent disability, and mortality representing a major healthcare burden. aSAH vasospasm has been associated with inflammatory processes in the subarachnoid space, however, the underlying cellular mechanisms are poorly understood. Blood products and vessel wall injury have been shown to trigger macrophage recruitment around the time of aSAH vasospasm. During our preliminary feasibility analysis, we collected tips of devices used in cerebral angiograms and endovascular interventions and processed them for RNA in the Johnstone Lab at Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at Virginia Tech Carilion. We were able to detect signal for housekeeping gene B2m as well as macrophage marker CCR2 and endothelial cell marker CDH5 via qPCR. This data indicates that cellular material including macrophages and endothelial cells is present on the endovascular devices and thus can be used to further study the role of immune cells in aSAH. Considering recent evidence that macrophages can communicate with other cell types and modulate their functions via gap junctions (GJ) - cell-to-cell communications made of connexin proteins such as Cx43 -, we hypothesize that recruited macrophages may be directly communicating with vascular smooth muscle cells after aSAH to modulate their contractile responses leading to the development of vasospasm. To test this hypothesis, we will study immune cell burden, Cx43 and contractility marker expression dynamics in aSAH patient cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and endovascular device tissue and their associations with vasospasm indices and clinical outcomes. This study has the potential to provide the first direct human evidence of the Cx43-GJ communication control of aSAH vasospasm opening avenues for novel vasospasm marker and therapeutic development.

The potential clinical benefits of the proposed study are two-fold: 1) developing a basis for early detection of vasospasm and follow-up of aSAH treatment responses via determination of immune cell-Cx43-GJ signaling status in CSF and endovascular device material, and 2) Identifying a novel therapeutic strategy for aSAH vasospasm treatment via modulation of Cx43-GJ cell-cell communication.

Carilion Clinic treats ~60 aSAH patients yearly. Nearly all of them undergo endovascular intervention for aneurysm diagnostics and/or treatment and majority require external ventricular drain (EVD) placement. We will enroll and consent patients with confirmed aSAH who require external ventricular drain (EVD) placement for CSF diversion. The group assignment will occur either when a subject has a vasospasm event recorded during the first 10 days of their hospitalization (enrolled in vasospasm group) OR on day 10 of their hospitalization if they have not had a vasospasm event recorded (non-vasospasm group). Study members will be reviewing enrolled subject charts daily to determine whether or not there is a vasospasm event recorded and will perform study activities accordingly. All aSAH patients will be treated following the standard of care, including close monitoring in the intensive care unit for up to 21 days, daily nimodipine treatment, EVD placement in cases of hydrocephalus, and daily transcranial Doppler flow velocity (TCD) assessments. The power analysis with an effect size of 0.2 and significance level of 0.05 determined that a total sample size of at least 36 patients (18 per group) is needed to achieve the desired power of 0.8. All adult patients with aSAH treated at Carilion Clinic will be considered for inclusion in the proposed study regardless of their sex or age. No vulnerable groups will be excluded from the study and participants will be considered for inclusion solely based on proposed criteria.

____________

The Effect of Dextrose 5% in 0.225% Sodium Chloride (D5 ¼NS) on Postoperative Chronic Subdural Hematoma Size and Recurrence Rate: a Prospective, Randomized, Double-blinded, Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial

PIs: Kristine Ravina, MD, and Eric Marvin, DO

How can we improve recurrence rates of chronic subdural hematomas to reduce need for surgical intervention? We hypothesize that Dextrose 5% in 0.225% Sodium Chloride (D5 ¼NS) will increase the intracellular brain volume and water content post-operatively, reducing the residual subdural space that is created by evacuation of the chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH), and that this, in turn, will reduce the hematoma volume that will then potentially lead to improved functional outcomes, reduced hospitalization time as well as the reduced rate of symptomatic recurrence requiring redo surgery.

Additional Information